Based in Mexico. Writing about culture, human rights and world affairs

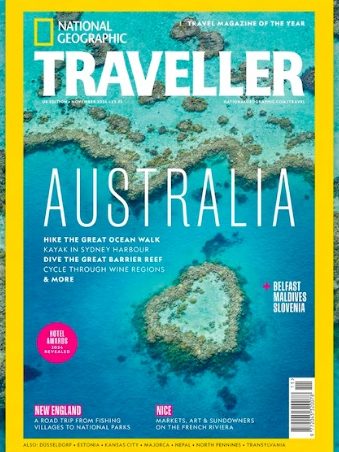

Work published in: The Guardian I National Geographic I CNN I BBC I Los Angeles Times I Daily Mail I Al Jazeera I The Daily Telegraph I Yahoo Living I Mexico News Daily I Mexico Living

Carlos Perez, a 30-year-old Colombian migrant from Bogota, was on track to reach the United States border with his wife and 11-year-old son by the new year.

The trouble came, however, when his wife became overwhelmed with fatigue as they reached the city of Tapachula in southern Mexico. By that point, they had travelled 2,500km — more than 1,550 miles — on foot.

So, Perez bought a bicycle. Often, he pedalled while his wife and child sat on the handlebars. On treacherous roads and at night, Perez walked alongside them as they rode slowly through darkness.

But a road accident in mid-November tore the skin from his shins and bloodied his wife and son's arms.

Founded in 1288 as a fishing village, Düsseldorf has evolved into an unofficial capital of western Germany, cultivating a reputation for fashion, finance and artistic flair along the way. Today, the city speaks to both its past and present — nowhere more so than in and around its Altstadt (Old Town), one of 50 districts.

Here, ancient taverns rub shoulders with contemporary galleries and electronic music clubs. Sheep graze on city-centre meadows, sharing the banks of the River Rhine with busy cultural celebrations. November marks the beginning of two popular ones: the Christmas season and ebullient Carnival, which culminates in a week-long celebration around Easter.

"The VW Beetle evokes memories of years gone by, but in Mexico it’s still part of the present"

CNN

August 2024

Photos by Mirja Vogel

In today’s world of autonomous cars, keyless ignitions and charging ports, it’s hard to imagine just how big the tiny, two-door Volkswagen Beetle once was.

But in Mexico, where the last Beetle rolled off the production line at Volkswagen’s flagship factory in Puebla in 2003, the plucky car lives on. Reinvented and reinvigorated by its cultural legacy, Mexico is one of the few remaining places where a taste of Beetle-fever still exists.

The car’s curvy, colorful exterior and air-cooled, rear engine propelled it to a level of fame and cult status which no petrol car will achieve again. While fond stories of the lovable vehicle roam in our memories, what was once the world’s best-selling car has all but disappeared from American roads, consigned to automotive museums and collector’s forecourts.

"Call me Betsa"

Los Angeles Times - July 2024

“Call me Betsa,” she says with a beaming smile, moments after putting down the phone with the Museo de Arte Moderno in Mexico City.

Betsabeé Romero had just confirmed her latest installation: an arched bridge constructed with the welded metal shells of five vintage Volkswagen Beetles, which have since been unveiled as a key piece in the MAM sculpture garden.

Romero’s work, which often centers on immigration, forced movement and borders, is getting a new level of exposure and recognition this year. Her solo exhibition in Italy, one of 30 events chosen as official extensions of the Venice Biennale, opened to baying crowds in April around the same time her giant public installations were being seen by millions of New Yorkers on Park Avenue. She installed five giant tractor tires there, each engraved with pre-Hispanic symbols that merge with interlocking patterns and images of Maya gods to help “dignify the memories of migrants.”

"The dried-up lake in Mexico fuelling fears of environmental disaster"

The Daily Mail

May 2024

Photos by Mirja Vogel

Standing on the bone-dry bed of what used to be one of the biggest lakes in Mexico gives one an eerie sense of what the end of the world could look like.

'Everything started to dry up a few years ago,' says farmer Carmen Ruiz, prodding the crumbling, cracked earth where Lake Constitucion used to be.

Occupying an area of more than 2,000 acres in the state of Queretaro, the lake was once larger than Gibraltar.

'There are children here who do not want to be black"

The Guardian

May 2024

Photos by Mirja Vogel

After 25 years, Angélica Sorrosa Alvarado is the last staff member left at Museo de las Culturas Afromestizas. She fears that soon it will be forced to close its doors

Angélica Sorrosa Alvarado is the curator, manager, tour guide, administrator, caretaker and cleaner at the Museo de las Culturas Afromestizas (Museum of Afro-Mexican Culture) in Cuajinicuilapa. “I am alone,” she says, gesturing at the cavernous halls of the museum, which she describes as “one of my proudest achievements”.

In the Costa Chica region, which is home to Mexico’s largest population of African-Mexicans, the museum is unique in the country. When it opened 25 years ago, it was heralded as recognition of the more than 2.5 million Afro-Mexicans in a country that had long overlooked them.

Now, however, the museum is now facing closure. Unpaid for 15 years and deserted by the founding committee who helped her create the space in 1999, Alvarado, 62, is fearful that she will soon have to retire. “They all left and now I am old and alone here,” she says.

'Four hundred years on, Mexico’s oldest Black community struggles to survive'

Al Jazeera

May 2024

Photos by Mirja Vogel

Outside Mama Cointa’s home where she has lived for almost all her life, guests have gathered to celebrate her 101st birthday. Her friend Victor steadies her quivering hand with his own while she tilts a ribbon-wrapped bouquet of wilting flowers to her nose. Her son Don Amado ushers visitors inside their family home.

“Our home is the last of its kind here,” Amado said, ducking underneath a sheet of thatched palm leaves hanging over the entranceway to a windowless, one-room house, where he was raised by his mother, Mama “Cointa” Chavez Velazco, in the village of Tecoyame, Oaxaca.

“But it may not be around next year. There is no support to help us, no money to maintain it as the climate becomes more extreme and threatens us more,” Amado added, before stealing a glance at his mother, whose milky blue eyes have begun to flood with tears.

“We are forgotten.”

The world's most valuable radish

BBC Travel

November 2023

Photos by Mirja Vogel

At Oaxaca's Night of the Radishes, freshly dug radishes are elaborately hand-carved for a holiday competition like no other in the world.

The radishes grown for La Noche de Rabanos (The Night of the Radishes) in Oaxaca, Mexico, are a world away from the small, thin, red and white sliced radishes that are commonly found alongside lime wedges and bowls of salsa on the tables of most taco restaurants in Mexico.

In fact, most of the 20 tonnes of giant, overfertilized radishes harvested in the days leading up to Christmas aren't edible. Instead, they're used as artist's canvases and hand-carved into the most intricate and elaborate festive scenes for a competition like no other in the world.

For the event, which is held annually on 23 December and is celebrating its 126th edition this year, the competition countdown for hundreds of Oaxacans begins with the radish harvest on the morning of 19 December, just four days before final designs are judged and a winner is chosen.

Defiance over danger as Mexico celebrates 'third' gender

Los Angeles Times

November 2023

Photos by Mirja Vogel

Throughout the weekend of Nov. 17, the 48th annual celebration of Mexico’s third gender — the “muxes” — took place in Juchitan de Zaragoza in Mexico, the country with the second-highest murder rate of trans and gender-diverse people so far this year.

Muxes — pronounced “mu-shay” are born biologically male, but live and embody traditional feminine characteristics and roles in their society.

A town legend paints one story of how muxes were created. During his trip around the world, the patron saint of Juchitan, San Vincente Ferrer, carried three bags with him. The first contained male seeds, the second female and the third contained a mix.

But as Ferrer reached Juchitan, the third bag split, and from the thousands of seeds that spilled onto dry earth grew the muxes — Mexico’s third gender, native to the southern Mexican region.

High-profile murders inspire calls for justice

Al Jazeera International

November 2023

Photos by Mirja Vogel

Felina Santiago was cutting hair in her salon when she heard that one of her oldest friends, Oscar Cazorla, had been stabbed to death at the age of 62.

“I was paralysed with pain,” she recalled. “I knew we had lost a pillar of our community that day.”

Santiago and Cazorla both belong to Mexico’s muxe community, pronounced “mu-shay”, made up of people who identify as a third gender, neither male nor female.

Traditionally, in Indigenous Zapotec society, muxes have been respected, even celebrated. But Cazorla’s murder in 2019 — along with the death of another prominent non-binary figure this month — has left the community shaken, fearful of further violence.

The latest high-profile incident came on November 13, when Jesus Ociel Baena, Mexico’s first openly non-binary magistrate, was found dead at home with multiple wounds.

Remembering lost loved ones in Oaxaca on Mexico’s Day of the Dead

Al Jazeera International

November 2023

Photos by Mirja Vogel

Paola Cruz and her nephew, Nicolas Sanches Gallardo, made a deal when they were kids playing in the hills of Oaxaca, Mexico.

They agreed that, when one of them died, the other would seek out a mariachi band to play their favourite Mexican songs at the funeral.

But Nicolas warned Paola that if he died first and she didn’t honour the pact, he would travel back to the world of the living on Dia de los Muertos — just to give her the scare of her life.

Paola is now 70, her short silver hair trimmed tightly above her dark, soulful eyes. She remembers the last Day of the Dead she spent with Nicolas, her junior by only six years.

Nicolas, his wife and his children had gathered at Paola’s house in the Santa Rosa district of Oaxaca for a holiday feast: handmade tortillas, slow-cooked beans, Oaxacan stews and pan de muerto, a sugar-encrusted bread that Nicolas made specially for the occasion.

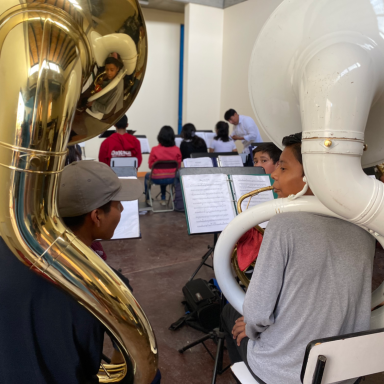

The Mexican street orchestra trading violence for violins

The Daily Telegraph

September 2023

Photos by Mirja Vogel

Since 2011, Santa Cecilia Music School has brought music education to a tough Mexican town. So can it repair the damage?

Armando* used to kick plastic bottles around the mountain of rubbish in the town of Vicente Guerrero in Oaxaca. He left school aged 11, fell in with a bad crowd, and soon he’d watch his friends cut the same bottles in half and fill them with solvents before mixing them with guava juice and inhaling the mixture deeply. They would pass into a dreamy, semi-conscious state for several minutes, refilling the bottles throughout the day.

“I saw how my friends got hooked on drugs and how quickly fights broke out. Kidnappings and burglary were common too. I didn’t think much about it because it was so normal here.”

He continues: “One day, my mum dragged me away and brought me to the door of the new music school in the centre of town, where I had my first tuba lesson. Playing the tuba relieved a lot of stress inside me.”

In 2014, Armando enrolled at the Santa Cecilia Music School, which was founded from rubble in 2011 to combat gang violence, crime, and children’s drug abuse in one of the poorest and most violent areas of southern Mexico.

selection of my favourite recent articles

Since 2011, Santa Cecilia Music School has brought music education to a tough Mexican town. So can it repair the damage?

Armando* used to kick plastic bottles around the mountain of rubbish in the town of Vicente Guerrero in Oaxaca. He left school aged 11, fell in with a bad crowd, and soon he’d watch his friends cut the same bottles in half and fill them with solvents before mixing them with guava juice and inhaling the mixture deeply. They would pass into a dreamy, semi-conscious state for several minutes, refilling the bottles throughout the day.

“I saw how my friends got hooked on drugs and how quickly fights broke out. Kidnappings and burglary were common too. I didn’t think much about it because it was so normal here.”

Dressed in a black suit, Emy Saldana walks briskly towards the bank. She’s been working there for almost 12 months and done the same route hundreds of times. Today is set to be one of the busiest days of the month at the bank, and she’s their number 1 seller. She takes a breath. In just a few a months', she’ll be one of the branch’s youngest ever managers.

Four blocks later, and she arrives and quickly makes herself a coffee before exchanging hurried pleasantries with her colleagues seated a glass barrier.

Her coffee’s not gone cold before she hears the first glass smash. The glass panelled door shatters into the main entrance hall as two masked men beat the door in with a pair of hammers. Panicked screams mix dissonantly with the shrill of security alarms, and Emy freezes.

Marcelo Castro Vera is a "rebel" making wines using the ancient technique of fermentation in clay pots in the mountains of Guanajuato .

Glasses clink and chatter echoes around the farm as the moon rises over a family gathering in Vergel de la Sierra, San Felipe, Guanajuato. A young Marcelo Castro Vera watches as his family toasts the Sunday night to a close. He enjoys the wine they are drinking, but what fascinates him is not the maroon “juice”, but how it has brought the people around him together.

Thirty years on and the very same landscape where a young Marcelo sat around a table with his family is now the birthplace of one of Mexico’s most exciting natural wines.

Founding a successful business in a foreign country is challenging. Combining it with an all-consuming philanthropic pursuit is even harder. Caitlin Ahern, an ambitious creative entrepreneur with a passion for protecting dogs, tells her story

There are 18 million street dogs in Mexico, more than double the amount of people living in New York City today. If these 18 million dogs were to come together to form one canine community, it would be one of the most populous cities in the world.

The sticky air is thick with the smell of chopped and charred agave plants at Palenque Don Goyo in San Baltazar Guelavila. Rain falls heavily on the rustic, family-run distillery which has been producing artisanal mezcal for 30 years. Water coats the leaves of 30,000 agave plants spread across 20 hectares of verdant land in this hidden valley in the Oaxacan hills.

The paved road which connects San Baltazar Guelevila to larger towns around Oaxaca city does not reach the Palenque Don Goyo. Instead, it was a muddy track laden with footprints of horses, donkeys and goats which narrowly got our car here this morning.

“If the rain continues like this, it won’t be possible to drive back today,” Rodrigo Martinez Mendez, grandson and heir to the family’s mezcal business, tells us as he unlocks two arched doors to a large barn-like building.

Every July, Oaxaca plays host to one of the most significant and popular cultural festivals in Latin America. La Guelaguetza, a joyous celebration of the region’s remarkably rich cultural heritage sees thousands of people from indigenous and regional communities across the state come together to celebrate their identity and traditions.

What follows, is a sensory extravaganza. Swirling dancers, mouth-watering food, dream-like clothing, tireless musicians, carnival-like street parades and infectious smiles are on show during every hour of the week-long celebration.

But behind the colourful parades of thousands of people from all corners of Mexico and around the world who visit Oaxaca for Guelaguetza, lies the work and dedication of individuals, families and communities who have spent much of the year preparing for the international spectacle. As the event grows every year, so does the responsibility of the communities to showcase their very best of their cultures. Theatrical moments hang in the balance. Preparation has never been so important.

Maria was a few months old when the seizures started. As electrical energy flooded her brain, the convulsions would render her body and mind unresponsive to her family around her. As she grew older, she would struggle to stand, walk and communicate and after time and multiple tests, she was diagnosed with cerebral palsy, the most common movement and motor disability in children.

Early intervention is critical when helping children with cerebral palsy. There is no cure, but certain medical treatments and therapy can make a big difference to a child suffering with the disease. Anticonvulsant drugs, for example, can also help with mood swings and emotional outbursts which Maria was particularly prone to. The medicine however is very expensive.

Like many families who have a child with a disability, Maria’s parents were forced to choose between the many treatments and medical services she needed to help treat the severity of her condition because of money. Lacking support, the outlook for Maria’s development was bleak until news of her tragic case reached Viridiana Pacheco, a young speech therapist originally from Mexico City who had just relocated to Oaxaca to work with disadvantaged children.

Towering palm trees brush against the salty night wind blowing inland from the Pacific Ocean in the secluded fishing village of Concepcion La Bamba.

Flashes of light from firefly colonies shimmer around Sergio Vasquez Lara as he quietly unpegs two fishing nets which hang like sails from a long clothesline suspended between two palms. It’s a little before 4 in the morning, and the clear July sky shrouds his path to the sprawling lagoon in darkness.

Sergio’s walked the same invisible path thousands of times since he was a young boy with his father, who taught him everything he knows about the virgin lagoon. It has been the lifeblood of the town for generations.

© Copyright. All rights reserved.

We need your consent to load the translations

We use a third-party service to translate the website content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details in the privacy policy and accept the service to view the translations.